Paul Revere’s Ride

The Midnight Ride

Original artwork by Cortney Skinner

In 2018 Walking Boston and Spyglass Books, LLC commissioned Cortney Skinner to produce a series of paintings covering the events of Paul Revere’s Midnight Ride. The objective of the project was to create the most historically accurate artwork to date covering Revere’s activities on April 18-19, 1775. Beneath each painting you can read Cortney’s notes regarding his research for that particular image and see references for the primary sources he utilized. The paintings will appear in the book Paul Revere’s Ride: An Illustrated History by Cortney Skinner set for release in 2025.

For the viewpoint of this painting, I chose a spot within the burying ground looking upslope toward the steeple of the Old North Church, then called Christ Church. Donald W. Olson and Russell L. Doescher of the Department of Physics at Southwestern Texas State University calculated that the moon was about 87% full that evening, according to their article in the April 1992 Sky and Telescope. I had the church steeple partially eclipse the moon as it illuminated the grave markers, grass and buildings at their edges. Current reference photos of the church provided us with the correct view of the steeple and an architectural research report produced by P. H. Batchler in March of 1978 (available through the Old North Church) showed a minor but important difference between the finials on the original steeple and those on subsequent versions.

In order to approximate the lay of the land and the positions of the buildings on the streets bordering the west side of the burying ground, I studied several maps and drawings of the period. “Clough’s Atlas of the 1798 Property Owners of the Town of Boston” gave me an accurate position for the streets relative to the church. The 1775 map drawn by Lieutenant Page of His Majesty’s Corps of Engineers, and the Bonner/Price map of 1769 helped me to estimate the placement and density of those buildings. Perhaps the most helpful drawing was that by Major Archibald Robertson of His Majesty’s Corps of Engineers, who drew the Copp’s Hill area from a viewpoint in Charlestown in 1776. This was one of a series of drawings, made with a trained eye by a skilled engineer which showed the characteristics of the land and gave a sense of the buildings around the burying ground. The tallest buildings seen in these drawings seem to have two stories plus a garret, but others are much smaller and have one story. Some have their ends while others have their backs at the edge of the burying ground.

There is no precise information about what buildings and houses may have been within this view from Copp’s Hill, but studying architectural records, early photographs and drawings of the period gives us an idea of the age and possible architecture of these structures which could have dated from both the 17th and the 18th centuries.

The grass and weeds are what might have been growing there in early spring, and that growth had not yet been cropped shorter by local Bostonians grazing their sheep on the hill.

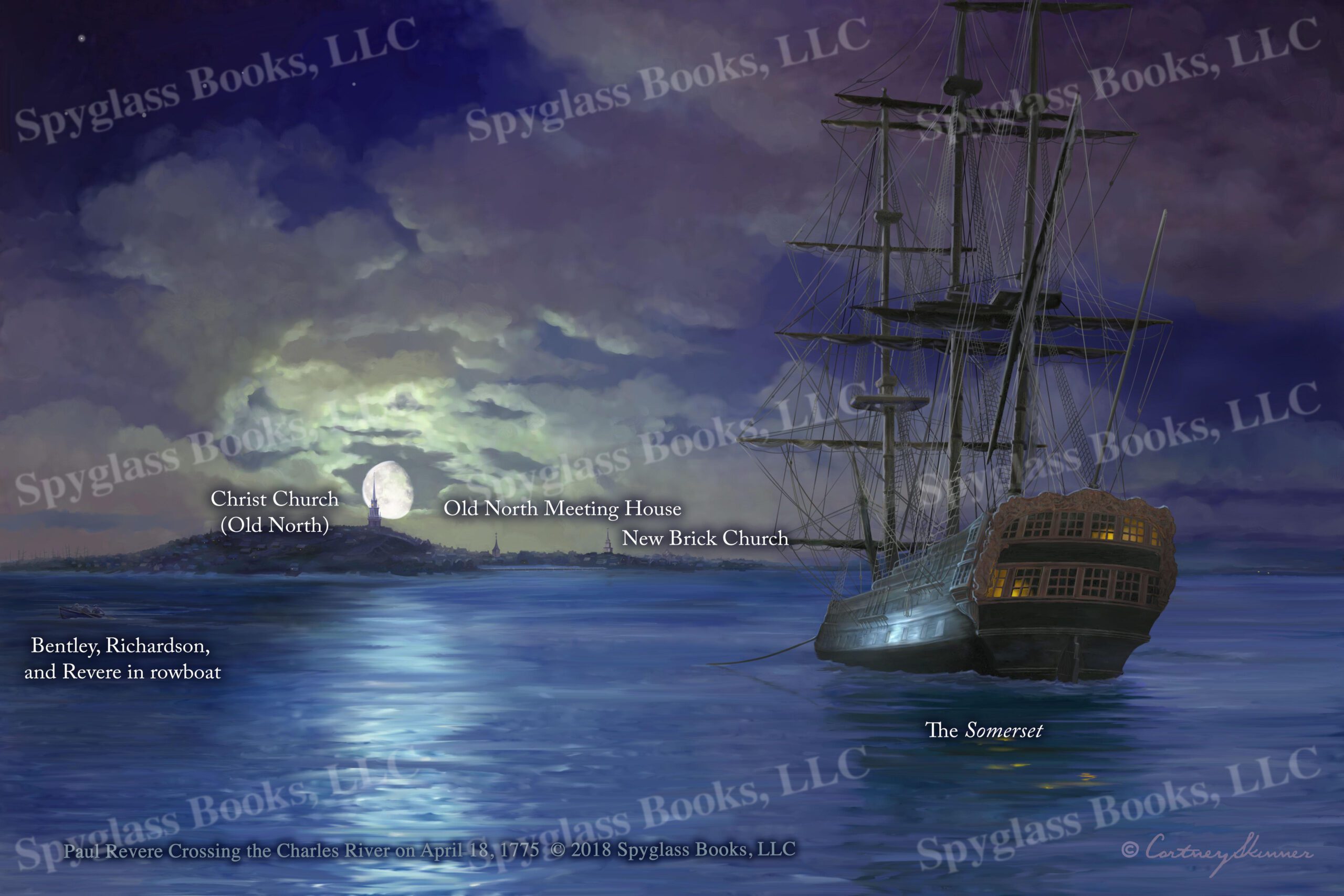

Paul Revere Crossing the Charles River on April 18, 1775

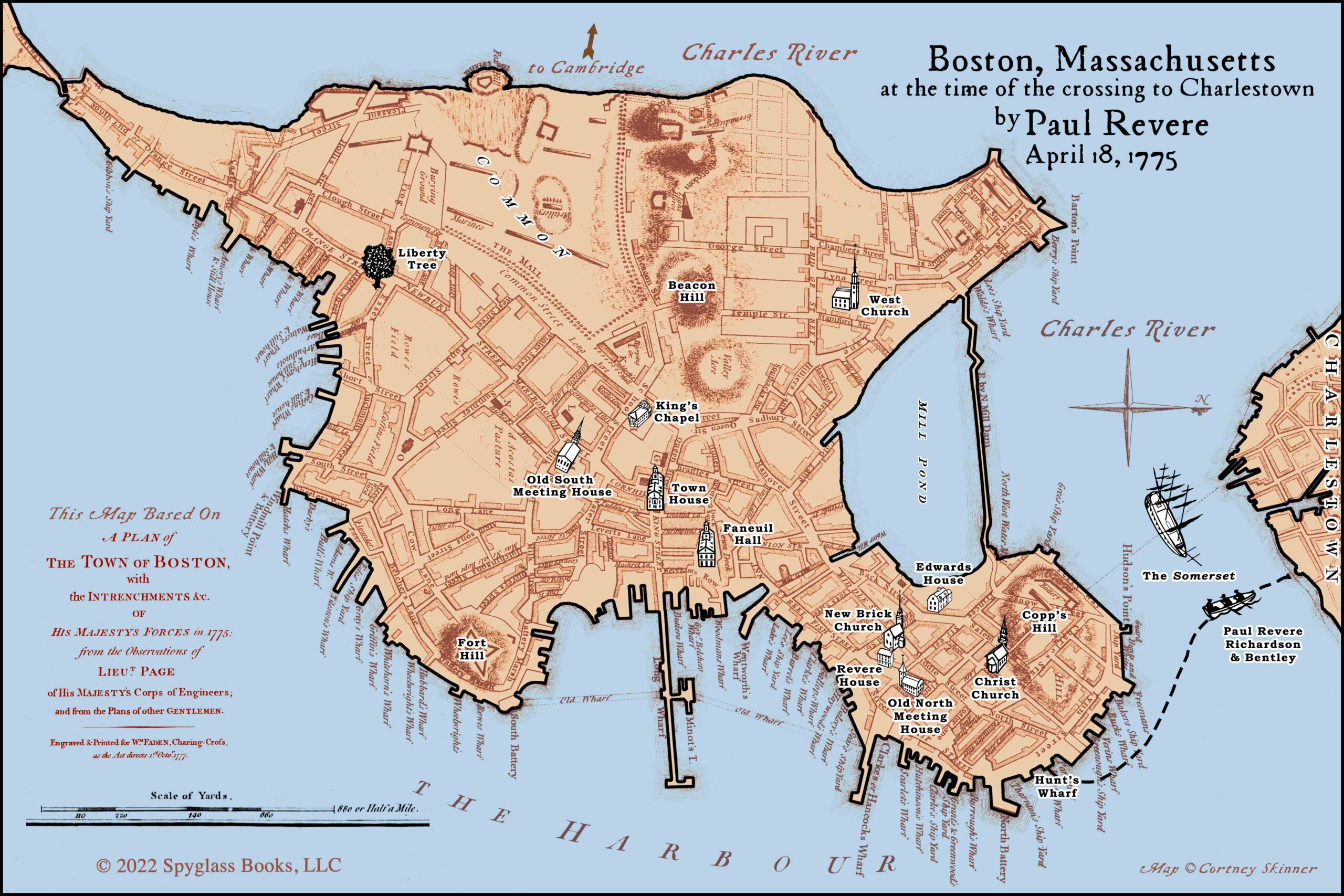

For this painting of Revere’s crossing past the British third rate ship of the line, “Somerset” and the view of Boston seen from the Charles River on April 18, 1775, several elements of research had to be carefully analyzed in order to set the scene accurately. Each part of this research is listed below for clarity, since there were so many of these elements to illustrate.

The Town of Boston

Using period maps, a topographical clay scale model of Boston was constructed, and the landscape recreated, including the hills, shoreline, the Mill Pond and dam. The positions of the taller, more important buildings whose cupolas, steeples and domes could be seen from the river were marked and located on the topographical model. Drawings by British engineers contemporary to this time were consulted in order to understand the density of the buildings in Boston, and how visually prominent these structures had been when seen from the river.

The Moon

Using detailed research by Olson & Doescher of the Department of Physics, Southwestern Texas State University, the phase (waning gibbous, 87% full) and position of the moon (altitude 6º, azimuth 121º) was accurately illustrated in the painting for the time that Revere was making his crossing.

Position of the Boat with Paul Revere, Joshua Bentley and Thomas Richardson

In order to approximate the position of the three men in the boat, I consulted Olson & Drescher’s research again. I plotted the possible route and timing of the boat which started from Hunt’s Wharf in the North End and could have been deflected by the rising tide as noted by Revere and almanacs of the period. In order to get an idea of how the three men may have appeared that evening, models were dressed in 18th century clothing, lit by a spotlight at the same angle as the moonlight and then photographed.

The Somerset

Consulting the book “HMS Somerset 1746-1778” by Marjorie Hubbell Gibson, the construction, condition and position of the ship in the Charles River were researched. The Somerset was then painted by referencing a scale model of an 18th century ship similar to the Somerset, and measured drawings of the ship from the Royal Museums Greenwich. Lighting the model ship at the correct angle helped to recreate the look of the Somerset in moonlight.

Important Discoveries

The topographical model of Boston was lit by a single light source that approximated the azimuth and altitude of the moon according to Olson & Drescher’s research. Just as their analysis discovered, the shadow of Copp’s Hill would have been cast across the river, enveloping and hiding Revere and his boatmen from the eyes of the watch aboard the Somerset. Other significant possibilities that have not been mentioned before and that may have diminished the effectiveness of the watch aboard the Somerset were found in the book “HMS Somerset 1746-1778” by Marjorie Hubbell Gibson. According to the ship’s log, drunkeness was a serious problem, with a death from drinking occurring that January. Sickness and desertions depleted the crews of the ships in Boston Harbor, and discipline problems were occurring. All of this would have seriously impacted the crews’ morale and performance.

Perhaps the most interesting development that would have helped to cover any sounds made by Revere and his boatmen (who used muffled oars) was that the Somerset had been leaking badly, despite being caulked a month before. She had to have her pumps manned at all times, and the constant noise of the working pumps could have concealed any sounds coming from Revere’s position.

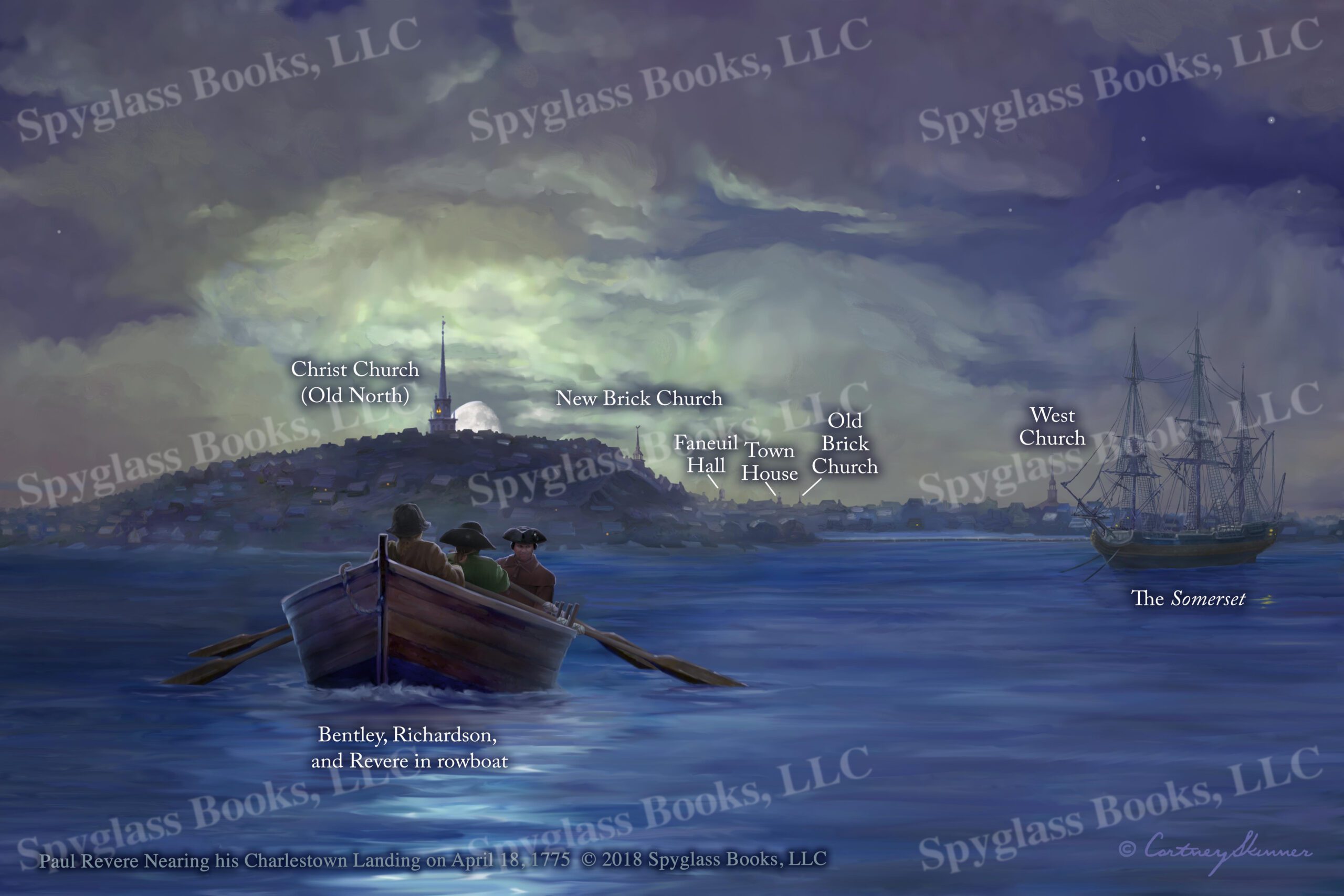

Paul Revere Nearing his Charlestown Landing on April 18, 1775

All of the items outlined in the earlier painting Paul Revere Crossing the Charles River apply to this one as well. In addition, for illustrating Revere’s closer approach to Charlestown, reference photos were taken of the topological model of Boston and the Somerset after calculating the changes in position and view of those elements. The clouds, moon and sky were also adjusted.

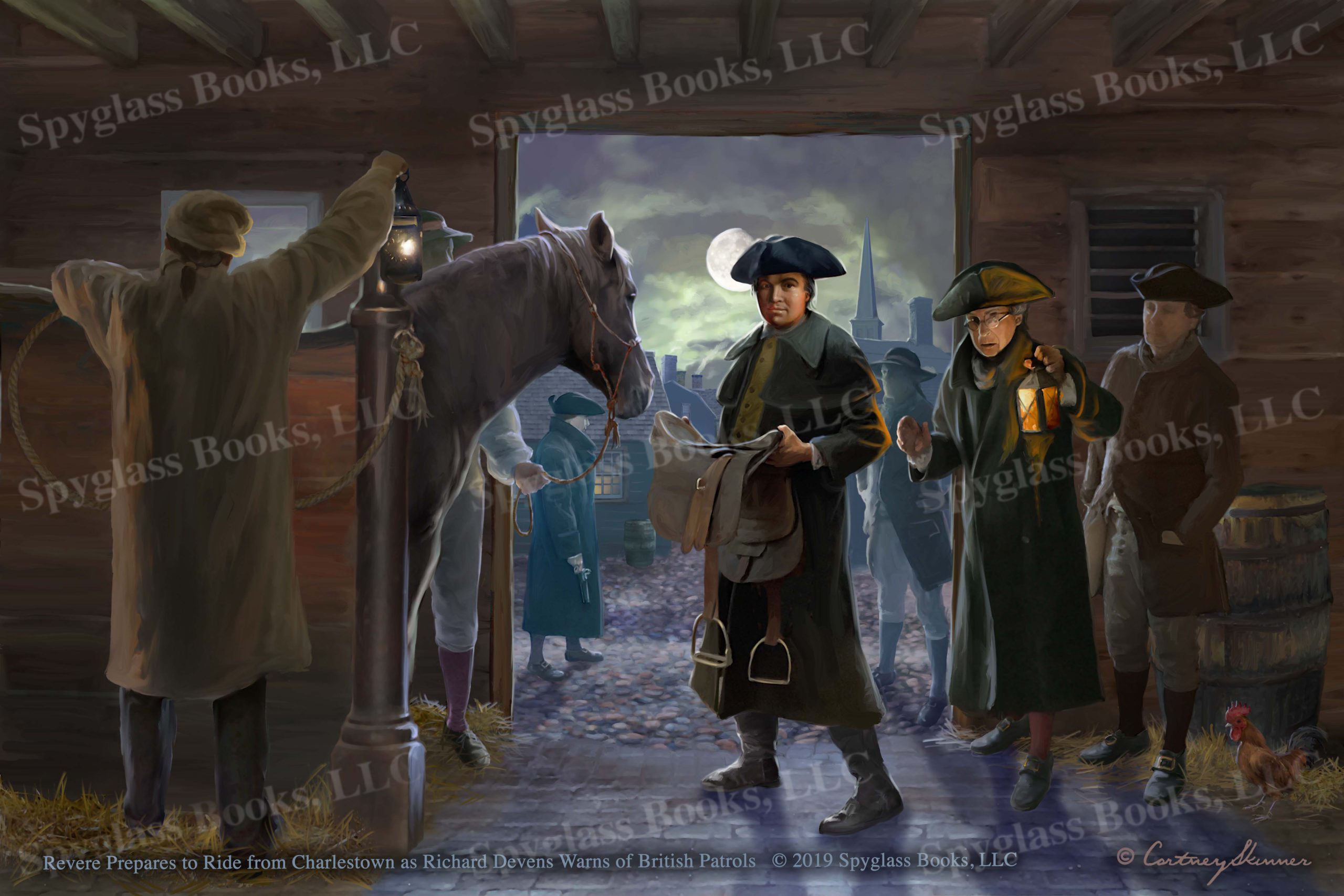

Revere Prepares to Ride from Charlestown as Richard Devens Warns of British Patrols

Paul Revere’s name and fame are well known, but the horse he rode during his celebrated ride is a bit of a mystery. Very little of substance is known about the animal other than unsubstantiated tales about its name and breed. Authors have embroidered on and elaborated about the nature and look of Revere’s mount, attempting to fill in the blanks with their own imaginations, but to illustrate this mysterious steed, a more cautious route was preferred. It was quite a challenge to reconstruct the scene with such a scarcity of information about the location, or indeed any specific details.

The horse belonged to Samuel Larkin of Charlestown, 74 years old at the time. His son, John Larkin, age 40, (later, a deacon) was a well-to-do merchant and was the person who loaned the horse to Revere. The Larkin’s wealthy status suggested that they could have used a sturdy and well-built stable to house their horses, wagons, or carriages. The exact locations of any of Larkin’s properties in 1775 is unknown, though after the disastrous fire that engulfed Charlestown during the Battle of Bunker Hill, John built a new house in 1795 (still standing) at what is now 55 Main Street in Charlestown.

With the stable as a setting (researched from recreated or extant 18th century examples), the town of Charlestown can be seen through the open door. The only clear information about Charlestown’s 1775 architectural makeup consists of four drawings by British officers done from Boston across the river. One drawing was done in 1764 and three in 1775. Three of the drawings show two and three-story buildings plus a very prominent church steeple, tall enough to be seen from many points in the town. One very interesting drawing shows the steeple engulfed in flames and another shows the town devastated, the steeple gone and wooden structures destroyed, but the brick structures, walls, and chimneys are still standing, revealing something of the basic architecture in that part of the town. With that information, a basic skyline could be recreated along with the prominent church steeple and the moon at its phase and elevation as previously researched. According to the Charlestown Historical Society, in 1716 Market Square was paved with cobblestones. As this event is said to have taken place near Market Square, those cobbles are shown.

Revere was spare about the details of his meeting with Larkin. He said in his 1798 deposition, “When I got into Town, I met Col. Conant, & several others; they said they had seen our signals. I told them what was acting, & went to git me a Horse; I got a Horse of Deacon Larkin. While the Horse was preparing, Richard Devens, Esq. who was one of the Committee of Safty, came to me, & told me, that he came down the Road from Lexington, after Sundown, that evening; that He met ten British Officers, all well mounted, & armed, going up the Road. I set off upon a very good Horse.” A Larkin family tradition says that the horse was a mare named “Brown Beauty.” Revere, a seasoned and experienced express rider, would have known how to choose his mount as well as the best available tack for a successful mission.

With Revere’s deposition as a framework, the late-night scene could be populated with a cast of protagonists. From the left to right; a stable hand holds a lantern to help illuminate the area. “Brown Beauty,” held by John Larkin, awaits the bridle as Revere approaches with a saddle, and is distracted by Richard Devens, age 54, an influential merchant of his day, who approaches with a lantern to warn Revere of the British patrol he met in Lexington. Next to Devens, warming his hands in his pockets on this chilly evening, is William Conant, age 47, a colonel in the provincial militia, who had helped Revere plan this evening’s events. Disturbed by the hubbub, a little rooster a “Nankin Bantam” (a popular breed of fowl of the period) looks on.

In the street outside the stable are two sentries. The Sons of Liberty and Committees of Correspondence were very careful about keeping this mission a closely held secret. It seemed logical that men would be stationed outside the stable to guard against prying eyes or overly curious townspeople. Once Revere trotted away on his expedition to Lexington, the stable doors closed, the Charlestown streets went quiet and the townsmen went back to their homes, nervously awaiting what might come next.

In order to create the illustration of Paul Revere eluding the British patrol in Charlestown, I was fortunate that in 1775, Henry Pelham (1748-1806) had created a very detailed map of the area where the event took place. I was additionally lucky that Revere himself had written two depositions, in 1775 and 1798, which detailed his ride and more importantly for this illustration, certain landmarks that matched features on Pelham’s map. There were also some interesting background particulars that connected Revere to Pelham, and to one of the features of the map which had an interesting story in itself.

Pelham and Revere were very well acquainted. In 1770, Pelham had created an engraving of the Boston Massacre, lent it to Revere who copied it without crediting him and then released his own version a week before Pelhams’ version went on sale. Pelham was a loyalist, later leaving Boston for England in 1776, so it’s a bit of irony that his map combined with Revere’s depositions gave me the information I needed for an accurate portrayal of the event.

As with the previous paintings of the stages in Revere’s ride, I used information about the phase, height and position of the moon to create the lighting effects and the length of the shadows cast by the protagonists.

The road seen in this painting is the road to Cambridge, Revere’s original choice for a route to Lexington. According to Pelham’s map, there were swampy tidal areas and a mill pond next to the road which can be seen at the left. Charlestown Common is at the right behind the stone wall. This entire area is now in modern-day Somerville.

Revere said in 1775, “I had got allmost over Charlestown Common towards Cambridge when I saw two officers on horse back standing under the shade of a Tree, In a narrow part of the Road. I got near enough to see their holsters & Cockades. When one of them started his horse towards me and the other up the Road as I supposed to head me, I turned my horse short about & Rid upon full gallop for Mistick Road, he following me about 300 yards, and finding he could not catch me, stopped.”

A group of trees where the officers were hidden were noted on Pelham’s map and appear in the left background. The officer trying to “head” Revere can be seen galloping up the road in the distance. Revere’s mention of cockades informed me somewhat of the uniforms that the two officers might have worn and you can see the cockade on the near officer’s hat. I painted him with his flintlock pistol drawn, since Revere mentioned “holsters,” and, as noted by Revere about his capture later on, British officers were not shy about drawing their weapons when needed.

In Revere’s 1798 deposition, he said, “After I had passed Charlestown Neck, & got nearly opposite where Mark was hung in chains, I saw two men on Horse back, under a Tree. When I got near them, I discovered they were British officers. One tryed to git a head of Me, & the other to take me. I turned my Horse very quick, & Galloped towards Charlestown neck, and then pushed for the Medford Road. The one who chased me, endeavoring to Cut me off, got into a Clay pond, near where the new Tavern is now built. I got clear of him…”

That “clay pond” is where the officer’s horse is getting bogged down, ending his pursuit.

One important landmark I used for this painting is the gallows which can be seen just to the right of the officer. This detail, noted in this painting, might be the first time that the place where “Mark was hung in chains” and the gallows on the Pelham map, have been reconciled as being one and the same.

Mark was an enslaved African-American man who had, in 1755, been convicted of murdering his cruel master in Charlestown, executed by hanging in Cambridge, and then his body “hung in chains” at the Charlestown Common as a warning to other enslaved people. Revere was 20 at the time of the trial and probably knew Mark who had visited Clark’s Wharf where Revere’s family lived at the time. The trial was a sensational one, evidently well remembered even decades later, since Pelham placed the gallows on his 1775 map, and Revere noted this sad landmark in his 1798 deposition. I can only assume that nothing was left of Mark’s body by 1775, but the strongly built gallows remained. The gallows on Pelham’s map helped me to locate the structures seen in this painting, as well as some of the trees seen in the background. The rest of the landscape is conjectural, as Pelham’s map and Revere’s description left off and artistic interpretation took over.

Paul Revere’s Ride on April 18-19, 1775

Making this iconic scene as authentic and accurate as possible was a challenge since there is so little information about exactly what Revere encountered along his route from Charlestown to Lexington. Setting the scene was important. Using detailed research by Olson & Doescher of the Department of Physics, Southwestern Texas State University and a program written by Torsten Hoffmann, the altitude, phase of the moon, as well as the length of the shadows that the moon had cast that night could be calculated very accurately. A landscape representative of Revere’s route was created, using architecture of the period, rail and stone walls that were in such great profusion back then, and a terrain typical of the area over which Revere traveled. The ground was muddy that evening and early morning, due to the showers that were reported in several diaries of that day, and so we see moonlight reflected in the soggy ground. According to Revere’s words in his letter to Jeremy Belknap, circa 1798, he wore his “Boots and Surtout” that evening, so those items of clothing, along with his hat and breeches, typical for that period, are illustrated being worn by Revere. The horse’s tack is typical of that era. Completing the scene are a few citizens, roused by Revere or already awake and alert due to the many previous rumors about the possible incursions into the countryside by the British regulars.

Paul Revere Arrives at the Clarke Parsonage in Lexington on April 19, 1775

Several elements for this painting had to be carefully researched and referenced before committing them to the final composition. The information from fieldwork and analysis by others helped to construct and confirm this accurate depiction of that morning’s events. The items researched appear below.

The Moon

Using detailed research by Olson & Doescher of the Department of Physics, Southwestern Texas State University, the phase of the moon (waning gibbous, 87% full) was accurately illustrated in the painting for the time that Revere arrived at the Clarke parsonage. Using a program written by Torsten Hoffmann, the direction and length of the shadows that the moon had cast that early morning could be calculated very accurately. The bright moon is reflected in the house’s upper windows.

The Clarke Parsonage

The 2007 Historic Structure Report for this building provided many interesting facts, detailing the structural changes that have happened over time. The still extant building stands on the original spot it had occupied in 1775, however several details of the building as it looks today, had to be taken back in time to that early morning on April 19th. The original windows probably had “nine over nine lights.” A theory proposes that that the door to the ell, with twelve raised-field panels, might have been the original front door, so that door was restored to what is thought to be its original position in 1775, at the front. The house is painted a yellow ochre with contrasting white trim. All is tinted with a blueish hue due to the cool bright moonlight.

Revere and His Horse

According to Revere’s letter to Jeremy Belknap, circa 1798, he wore his “Boots and Surtout” that evening, so those items of clothing, along with his hat and breeches, typical for that period, are illustrated being worn by Revere. The horse’s tack is typical for that era. For Revere’s horse, a trip to a riding stable and an experienced horseman provided an opportunity to reference a horse in a dynamic posture of being dismounted in a hurry.

Sergeant William Munroe and His Men

According to his deposition, Sergeant William Munroe, learning that there were nine British officers in the area, “immediately assembled a guard of eight men, with their arms, to guard the house.” Munroe is challenging Revere, not immediately knowing who he is, and one of his men can be seen behind him. Both are dressed and armed with clothing and firearms of the time.

Occupants of the Parsonage

Within the house downstairs is the room where John Hancock and behind him, Sam Adams were when Revere arrived. Both are based on contemporary portraits. The wallpaper and bed, accurate for that time, can be glimpsed through the window. On the floor above them are Hancock’s fiancee, Dorothy Quincy and Hancock’s Aunt Lydia, also based on contemporary likenesses. The Reverend Jonas Clarke can be seen in the room which was known as his study. His likeness is based on a contemporary silhouette.

Paul Revere Enters the Clarke Parsonage to Meet With Hancock and Adams

With help from historians familiar with the events, authors who have written about that historic day, and the Lexington Historical Society – and after much collating and sifting of available research – it was possible to create an illustration of how this scene might have looked in the early morning hours of April 19, 1775.

The particulars required in an illustration such as this one are difficult to discover in historical texts, or in personal journals of the period. The final painting is a balance between making an interesting picture and being as true as possible to what is historically known about the event.

The Lexington Historical Society gave special permission for photographs to be taken in the actual room where Revere, Hancock and Adams met on April 19, 1775. Photos were taken from several vantage points and the appropriate ones were used as reference.

The room itself, today known as the “Hancock-Adams Bedroom,” was originally wallpapered in 1775. An image of an existing, surviving fragment of the wallpaper pattern was supplied to me by the Lexington Historical Society. That pattern was then extrapolated and extended. This made it possible for me to create how the completed pattern might have looked. In the illustration, the windows are recreated according to information in the Historic Structure Report for the Hancock-Clarke House, in which it says that the earliest windows probably had “nine over nine lights” as those shown in a painting of the house made c. 1840.

Some furnishings of the room are original to the Hancock-Clarke House and survive to this day. One item, the table, was in that room on that night, so I made it central to the scene. Hancock’s chair is original to the house, but it’s unknown if it was in that room on that night. Adams is seated in a similar chair, representative of the period.

It’s known that a tall case clock made by Nathaniel Mulliken of Lexington was in the house, and a representative example of that clock is presently in the room. A different, yet similar, example of one of Mulliken’s clocks is in the painting, so as not to suggest that the present-day example was there on that day.

As we view the scene, we are standing with our backs close to the rear wall of the ”Hancock-Adams Bedroom,” facing the windows at the front wall of the house. To the left, just out of the picture, is the fireplace which lights the room with a warm glow. Cool light from an almost full moon pours through the windows. A large bed is just out of the picture to the right. Paul Revere has just entered through the door at the left of the picture.

Revere is dressed in his greatcoat and riding boots as he noted in his depositions. He entered only seconds before and has taken his hat off in respect to the two other men in the room.

Hancock and Adams had just been at the window watching Revere’s arrival as Sergeant Munroe challenged him. Not knowing the message that Revere was carrying, they had stepped away from the window and back to the table in case they had to gather their belongings, don their coats, and leave in a hurry. Seeing that Revere’s demeanor was not communicating immediate danger, Adams has seated himself once again at the table to deal with the important documents he had been composing.

John Hancock stands in his shirtsleeves, concerned about the news that Revere brings. At this late hour and in this informal situation, he is without his wig, as seen in the Copley portrait of 1765. His natural brown hair is tied back in a short queue. Dorothy Quincy, his fiancée, had mentioned in her recollections that Hancock had been cleaning his gun that night. A flintlock pistol can be seen on the table along with refreshments for the long and tense evening.

Sam Adams’ exact actions on that night are not documented. However, in his cloth cap and with his glasses pushed up on his forehead, he is shown attending to some papers, not an unusual activity for someone as important to the patriot cause as he was.

To help with capturing the likenesses of the protagonists, the18th century portraits of Revere, Hancock and Adams by John Singleton Copley were analyzed by a program which converted these two dimensional images to three dimensions. These could then be turned and viewed at the angles needed for the painting.

The bureau seen to the right is original to the house. On the wall can be seen two framed etchings of Biblical scenes of the period. It’s not known what, if any, pictures were on the walls of Reverend Clarke’s rooms, but these two examples were chosen to give the room a more lived-in feel.

Sergeant Monroe, on sentry duty outside the house with his guard of eight men, is seen just outside the window casting a glance inside to the occupants of the room as he carries on with his duties on this significant day in history.

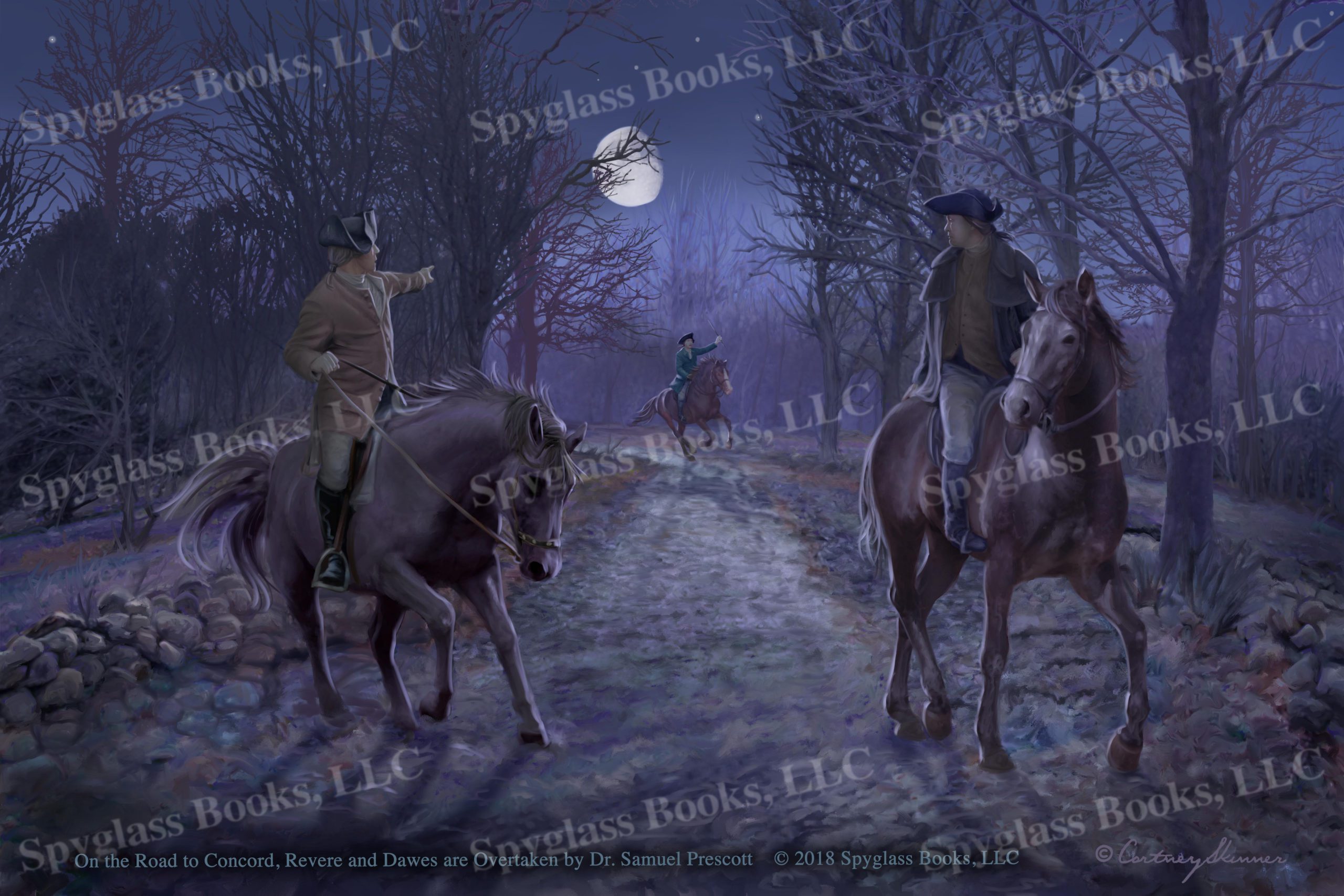

To set the scene for this dramatic meeting, a point along the route ridden by Revere and Dawes was chosen so that the moon would be behind the two riders as Prescott approached them unexpectedly. Using a program written by Torsten Hoffmann, the altitude, phase of the moon, as well as the length of the shadows that the moon had cast that early morning could be calculated accurately. According to Revere’s letter to Jeremy Belknap, circa 1798, he wore his “Boots and Surtout” that evening, so those items of clothing, along with his hat and breeches, typical for that period, are illustrated being worn by Revere. Dawes and Prescott also wear clothing suitable for the time and the weather. The horses’ tack is typical of that era.

Paul Revere and Dr. Samuel Prescott are Intercepted by a British Patrol

Paul Revere and William Dawes had just left the Clarke parsonage in Lexington after warning Samuel Adams and John Hancock, who were staying there, about the approaching British incursion from Boston into the countryside. After heading to Concord, they were soon overtaken by Dr. Samuel Prescott, age 24, a local physician and recognized by Revere as a “high Son of Liberty.” This is depicted in the previous painting.

Prescott was briefed by Revere and Dawes about their mission and agreed to help warn the houses along their route since he was well known by the inhabitants. As Dawes and Prescott stopped at a house, Revere continued on for about 200 yards when he spotted two British officers under a tree. He called back to Dawes and Prescott to hurry and join him since all three of them could likely overcome the two men. Soon, however, four armed British officers rode up and surrounded him, threatening Revere with death if he didn’t immediately stop.

Prescott rushed up to Revere, turning “the butt end of his whip” to use as a club against the British officers if needed. Dawes, seeing the British patrol, escaped across the countryside. According to some stories, he discouraged his pursuers from following by pretending that he had set up an ambush.

The moment that the painting illustrates is when Prescott brandishes the heavy metal handle of his whip and he and Revere are forced into a pasture through a gap in a fence line where two of the bars had been taken down by the British to allow entry into the pasture.

The British officers are all wearing surtouts or overcoats to better hide their bright red uniforms and identity. They had been part of a larger party that rode out into the countryside incognito to scout and intercept any patriot riders who had been sent out to warn of the British military expedition from Boston.

The entire group is illuminated by a lowering moon, at that time, about 28º above the horizon and casting long shadows over the fields. Revere stated in his deposition that the British officers “had taken down a pair of Barrs on the North side of the Road.” That fact gave me the information I needed for the position and angle of the moon which then allowed me to calculate the length of the shadows.

Revere’s deposition also mentioned that he later found out that one of the men who stopped them was Major Edward Mitchell of the Fifth Regiment of Foot. Mitchell’s regiment wore red coats with lapels or facings in “gosling green,” a pale olive color. Just a bit of those green lapels and red uniform show thorough the open collar of his surtout. All the British officers are armed with swords and pistols typical for the British army at the time.

In the back field can be seen more of the British patrol, ready to rush from hiding in the trees to help secure Revere and Prescott. Their plans were not to be totally successful.

Cortney Skinner’s artwork appears in books, magazines, comics and in films. He has illustrated a wide range of subjects including science fiction, classics, horror, fantasy, history, aviation, and children’s books. His landscapes, still lifes and portraits are found in private collections.

Skinner studied illustration at the Art Institute of Boston under Norman Baer, a second-generation student of Howard Pyle, (1853-1911) the famous Golden Age illustrator known for his historic illustrations of the colonial period. Beginning his career in the traditional art techniques of pencil, pen and paint, Skinner entered the digital art world at the turn of the last century.

Cortney’s fascination with the colonial period began when, in the third grade, his class was given a tour of the Revolutionary War period historic sites of his hometown of Cambridge Massachusetts. During the bicentennial, he started the first living history Continental Line Regiment, the 1st Massachusetts Regiment, Continental Line, requiring a great deal of research in order to construct the clothing and uniform of a soldier of the Revolution.

Nestled comfortably in the Shenandoah Valley by the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia, Cortney shares a creative life and abode with his wife, writer Elizabeth Massie. To learn more about Cortney, visit CortneySkinner.com.